As a survivor then carer during Liberia’s 2014-15 Ebola epidemic, Karwah inspired many; so does her death during childbirth — anguishing, preventable, sobering and focusing of attention on more chronic (though no less urgent) ailments, such as those afflicting healthcare systems in West Africa and low-resource communities.

MONROVIA, LIBERIA — On February 21, 2017, Salome Karwah — a key provider of care during the 2014-15 epidemic in Monrovia, Liberia and a 2014 Time Person of the Year — passed away suddenly. She reportedly succumbed to complications from childbirth. At the time of her death, she had survived not only the Ebola epidemic but also the loss of both parents to the disease.

Most readers outside (and inside) Africa were introduced to Karwah twice in late 2014. First, during the circulation of her autobiographical account as an Ebola survivor, which she wrote for Médecins Sans Frontières in October of that year. And then later in December, as part of a group of Ebola caregivers named, collectively, by Time Magazine as Person of the Year.

Karwah Among Persons of the Year

Even now, her account of survival is both an anguishing and inspiring read. It begins the way Ebola had often seemed to begin during the period, to suddenly enter a home as a debilitating and soon pervasive presence:

“It all started with a severe headache and a fever. Then, later, I began to vomit and I got diarrhea. My father was sick and my mother too. My niece, my fiancé, and my sister had all fallen sick. We all felt helpless.

It was my uncle who first got the virus in our family. He contracted it from a woman he helped bring to hospital. He got sick and called our father for help, and our father went to him to bring him to a hospital for treatment. A few days after our father came back, he too got sick. We all cared for him and got infected too. This is the way the virus works, person by person, cutting through families.”

By August of that year, most of the family were taken to an Ebola treatment center in Monrovia, where Karwah spent several weeks. In her account, she takes us through scenes and feelings of severe disorientation, caused by the fever and vomiting, caused by her isolation and eventual separation from her parents, but also caused by the diagnosis itself and the pain.

“After the lab test, I was confirmed positive. Your first thought is that this is the end of the world. I was afraid, because we had heard people say that if you catch Ebola you die.

I was feeling severe pains inside my body. The feeling was overpowering. Ebola is like a sickness from a different planet. It comes with so much pain, and it causes so much pain that you can feel it in your bones. I’d never felt pain like this in my lifetime.”

There is a palpable sense here that Karwah’s writing makes vivid a library of scholarship on the near inarticulateness of the human body in pain, as well as the sense, once achingly described by Susan Sontag, that the news of a terminal diagnosis can instantly make you feel like the citizen of another country, one now forever distant and distinct from your family’s native home. But Karwah’s account at once encapsulates and surpasses such theories of illness experience, in part because the Ebola epidemic of 2014-15 had demanded it: had in Monrovia enveloped entire bodies, entire families, entire homes and worlds with pain. Such that Karwah communicates to us the feeling she had, then, that the disease had arrived from another planet. For her, the facts that she, her sister, her niece, her fiancé were able to survive and walk out of the treatment center are also events that belonged to another realm. “God,” she writes, “could not have allowed the entire family to perish. He kept us alive for a purpose.”

Karwah Returns As Carer

Karwah returned to the treatment center approximately a month after she was discharged. Without planning to, she became known in her country and beyond it as an emblematic carer of Liberia’s most care-depleting epidemic: where the disease had so systematically decimated the nation’s professionally trained health personnel that it came to rely heavily on Ebola-immune survivors, at least those who chose to find their purpose in returning to the isolation wards to be among the patients, who had themselves come to resemble family.

It is worth noting, therefore, that Karwah’s account ends on two scenes that foreshadow her own passing less than three years later. The first scene reveals the ambiguities of return for a survivor; the other is willfully optimistic, and attempts to give meaning to her decision to return so soon as an immune carer.

“I arrived back home feeling happy, but my neighbors were still afraid of me. Few of them welcomed me back; others are still afraid to be around me — they say that I still have Ebola. There was a particular group that kept calling our house “Ebola home.”

I feel happy in my new role. I treat my patients as if they are my children. I talk to them about my own experiences. I tell them my story to inspire them and to let them know that they too can survive. This is important, and I think it will help them. My elder brother and my sister are happy for me to work here. They support me in this 100 percent. Even though our parents didn’t survive the virus, we can help other people to recover.”

Here, Karwah understands that the extended family structure of the neighborhood, once a seemingly natural extension of her parents, is no longer as openly available to her as before. The classic lesson is of course, that stigma always complicates, if not disrupts, such relations, all the more when the specter of virulent contagion is made real. But Karwah also learns of and feels her way towards a different place of community, one emerging from the epidemic itself, developing from what remains of her nuclear family (“my elder brother and my sister are happy for me… they support me 100 percent”) to include her new patients at the treatment center, who she comes to care for as if they were her own children.

With them she learns the caring, even curative value of repeatedly telling her story. Several doses of it a day, its own kind of supportive care, which provides not just inspiration. Not just the cajolement to eat or clean oneself. Not just the instruction to move whenever possible, and the aid to help one do so. But also concrete evidence to her patients and children of a possible future of survival, where they can see themselves having lived past the epidemic, just when she knows the diagnosis and pain would seem to close off their worlds completely. To the best of her newly trained, honed, and self-aware abilities, Karwah eventually constructed something anew from the stigma of being part of an “Ebola home.” And she seemed to extend that new edifice outward when she decided to lay out her story in prose and write to us.

Karwah in Context

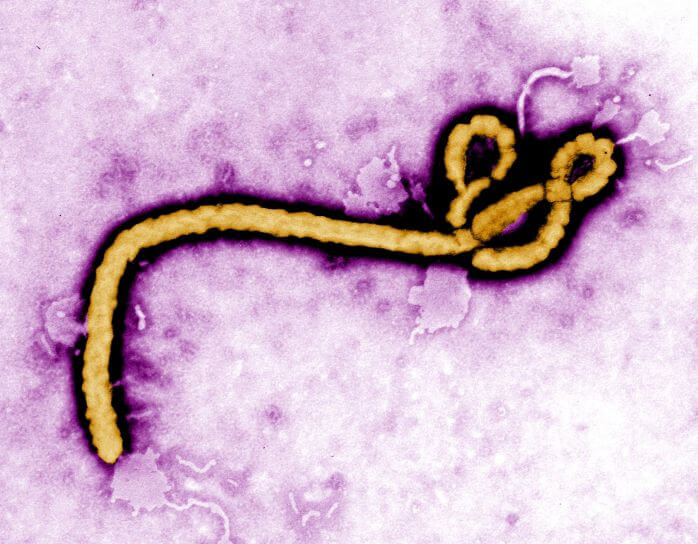

Karwah also served as a literal stop-gap for an infrastructure crisis that has plagued countries like Liberia for some time. To be exact, the exacerbation of the Ebola epidemic of 2014-15 had as much (or more) to do with the preceding debilitation of the country’s structures for care, as it may have had to do with certain behaviors that reportedly facilitated contagion. Where one must certainly account for the effects of living arrangements, home care, institutional skepticism, and burial practices on the increased transmission of the virus, one now knows to also mention and robustly discuss the insufficient number, distribution, and protection of healthcare personnel, the extensive weakening of health systems, and the poor response abilities of international public health and scientific communities. The uneven development of infrastructures of care has of course a historical, geopolitical, and economic dimension in the affected countries of Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, which had never been unknown by longtime healthcare and civil servants of the region, and had become an unavoidable fact to at least be acknowledged by the larger global community in 2014.

In fact, to the chagrin of public health and government officials as well as the suffering of many of their patients and constituents, uneven structures of care have not proven to be problems of acute, episodic concern, circumscribed only to the appearance and disappearance of disease outbreaks. In West Africa, they have indeed been proven to produce increasing racial and regional disparities in global morbidity and mortality rates, and this during normally healthy scenes of care. Maternal health has, to no one’s surprise, become a remarkably accentuated point of concern, taken up by a now continuous series of published studies and reports — there is The Lancet’s series one and series two, WHO’s Report on Trends in Maternal Mortality, Amnesty International’s moving 2010 report Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Health Care Crisis in the USA, and ongoing analysis from the CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System — with data showing women in sub-Saharan Africa and women of African descent living elsewhere dying at remarkably higher frequencies than their peers, colleagues, and generational cohorts. What such research leaves up for serious consideration is that it might now be a risk factor to be born a woman and of African descent in a number of state and socioeconomic settings, to then become pregnant or decide to have a child, to want to have children after surviving an epidemic or political or economic crisis, and then to enter into labor, either at home or in the nearest hospital.

Karwah Gives Birth

And so it was with Salomé Karwah. Despite her widely recognized work as a mental counselor, despite her earned proximity to health communities, despite the inspiring meaning she gave to her survival, and her chosen purpose to care for others who were both ill and isolated, her life was ultimately narrowed by her gender, her economic status, her country of birth, and then by her initial, month-long encounter with a disease. Two and half years later, on Feb 17, 2017, she delivered a healthy boy by cesarean section. She was discharged home three days later, and within hours lapsed into convulsions. Her husband and her sister rushed her to the hospital. But they found that none of the hospital staff would come near her. According to reports, on seeing her violent seizures and foaming at the mouth, the personnel recalled aloud her status as an Ebola survivor, and they gave her distance in lieu of fluids or treatment.

Karwah died the following day, with the hospital’s response to a past epidemic’s lingering stigma all but encapsulating her life’s meaning at the end, precluding any opportunity she might have had to survive complications from her pregnancy. What they wouldn’t do, what they wouldn’t treat or touch, was the gift she had given each of her patients: every day, every week, and every month of her work during the epidemic.