University of Texas has done a considerable public service in digitizing, cataloguing, and making available the papers of Gabriel García Márquez.

AUSTIN, TEXAS — When the University of Texas acquired the personal papers of Gabriel García Márquez, soon after his death three years ago, many in his home country of Colombia and beyond it expressed disappointment that the archive of one of Latin America’s greatest writers — and an open critic of American foreign policies — would end up in the United States. But the university’s Harry Ransom Center has done a considerable public service in digitizing, cataloguing, and making freely available about half of that collection, with an array of scans and photographs now visible to many in the world.

Spanning over fifty years, with more than 27,500 digitized pages, the Gabriel García Márquez online archive has now been made available, for free, to the wider public. The page scans and photographs make up approximately half of the author’s personal papers, acquired in 2014 by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin. And what one is able to find on using the searchable database amounts to a novel reader’s treasure trove.

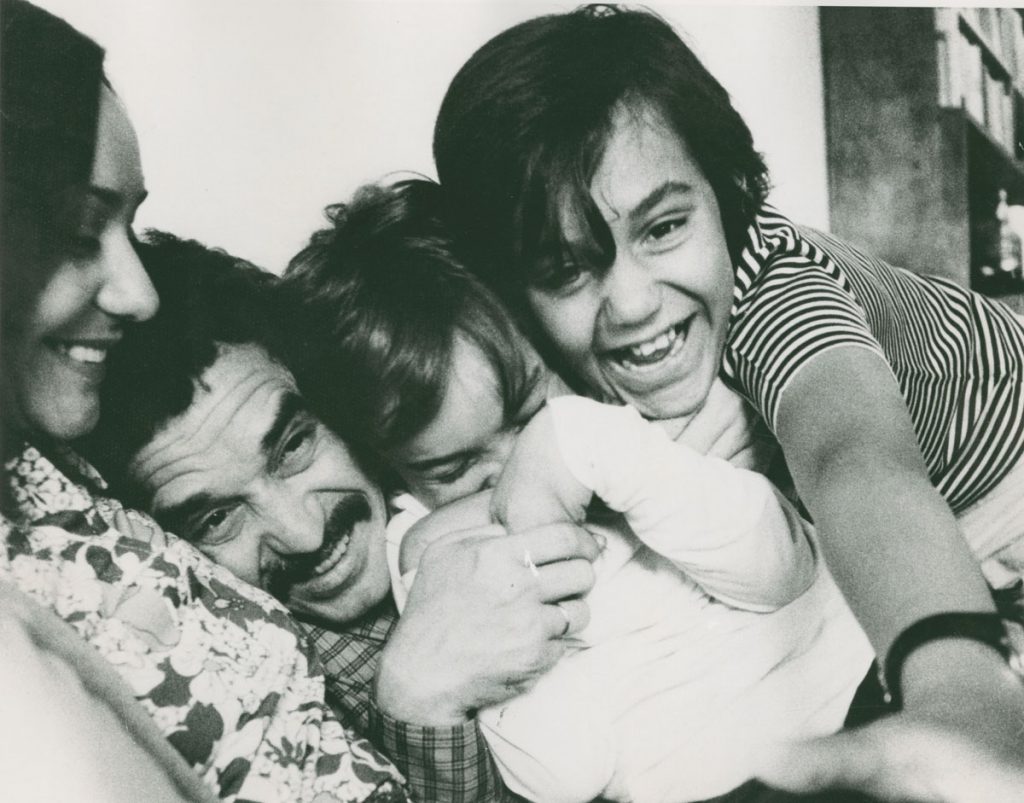

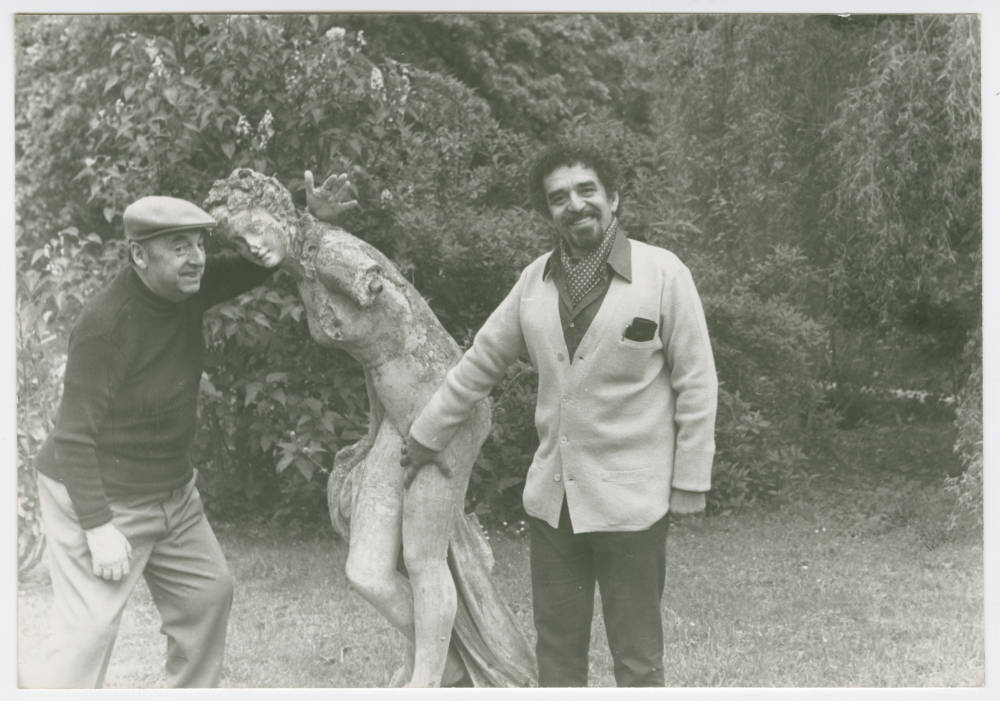

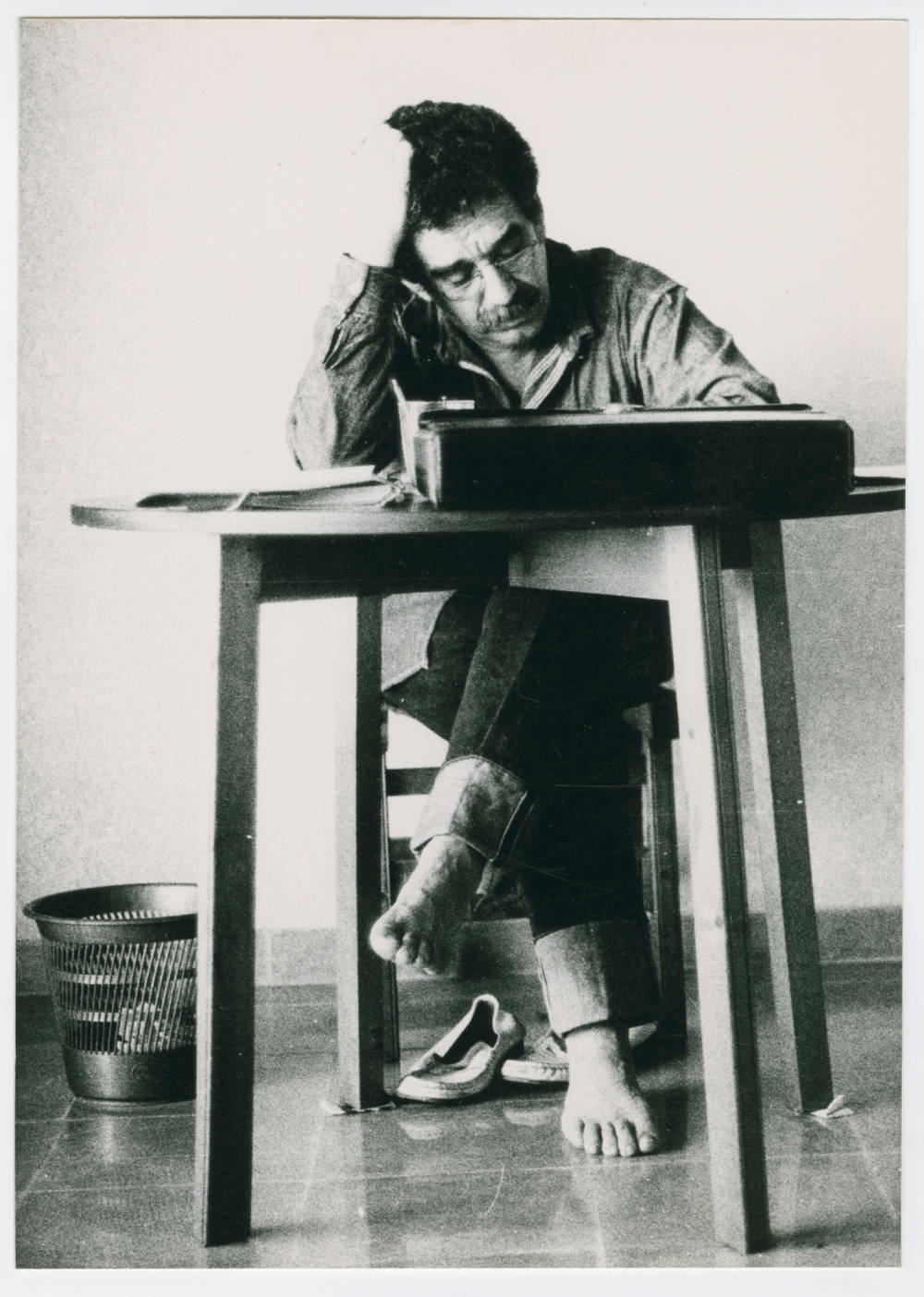

There are complete manuscript drafts of his most well known published works — One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), The General in his Labyrinth (1989), The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), Of Love and Other Daemons (1994) — and works he had not yet released. There are myriad number of photographs, in black-and-white, sepia and full color, that date from his early childhood through to his work as a journalist, his marriage and family life, his visting and play with friends as well as well known colleagues (Pablo Neruda, Fidel Castro).

Gabo as Boy

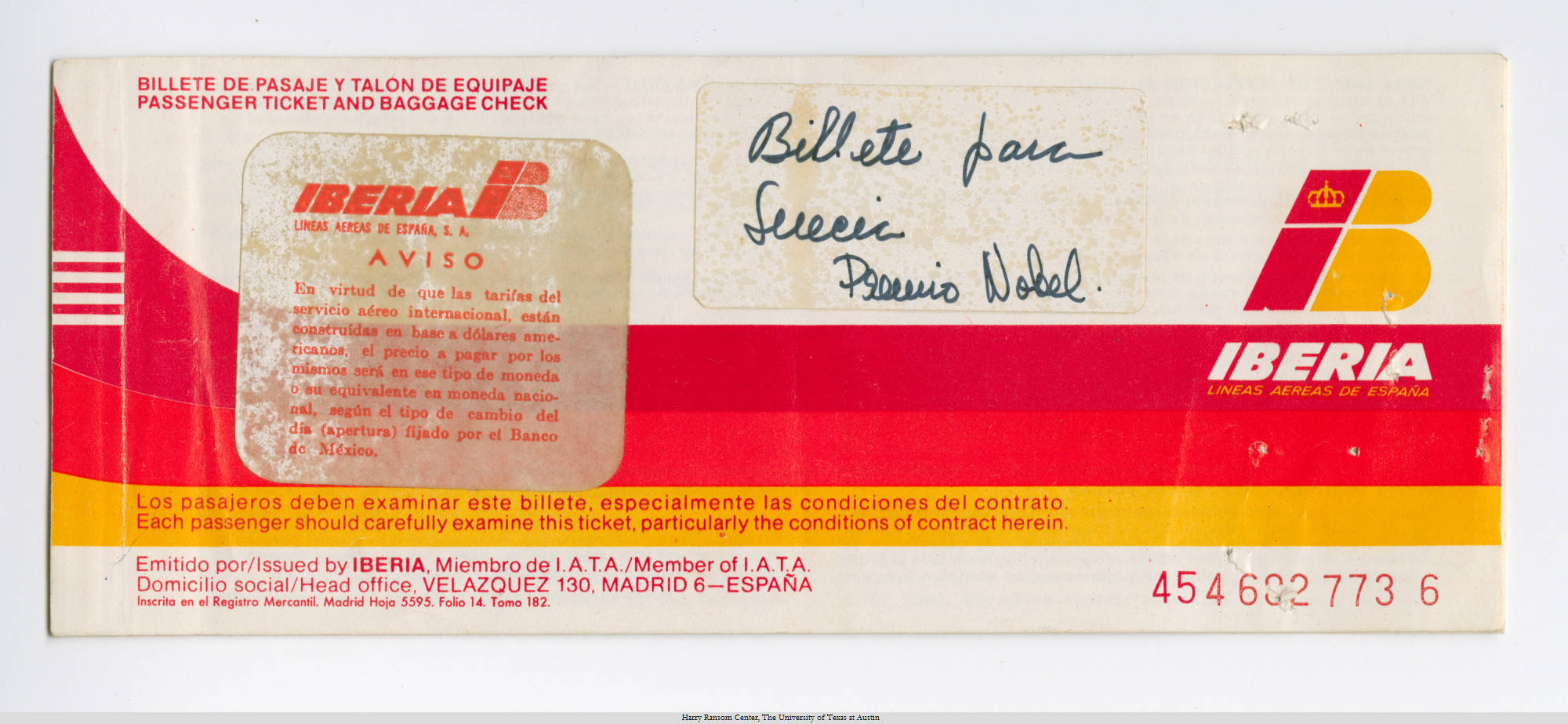

And for aficionados there is an assortment of scrapbooks, correspondence, clippings, notebooks, screenplays, printed material, ephemera, and an audio recording of García Márquez’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982, all within easy access and display via the Center’s fine cataloguing.

It is important that the archive is searchable for both English- and Spanish-language text. The university sought advice from specialists in its own Benson Latin American Collection on ways to describe the Colombian writer’s work in Spanish. And the entire project required 18 months of input from a wide range of personnel and expertise — librarians, archivists, scholars, teachers, students, technology staff, and conservators.

Another important source of expertise and support has been García Márquez’s family, acknowledged repeatedly in the Ransom Center’s press materials on the archive. “My mother, my brother and I were always committed to having my father’s archive reach the broadest possible audience,” said Rodrigo García, one of the author’s sons. “This project makes my father’s work more widely accessible to a global community of students and scholars.”

Gabo, La Familia, El Escritor

Rodrigo García’s comment is noteworthy given the recent history of the archive’s acquisition and placement in the United States. In a series of public responses to the news in 2014, perhaps best summarized in a pair of articles in The Guardian and The New York Times, several Colombian figures including academics, the minister of culture, and the director of the national library made known a palpable sense of disappointment at the home country not having the honor of housing the archive (“It’s a great pity for Colombia to not have them,” Mariana Garcés Córdoba told RCN Radio). The sought-for and much-quoted comments from the family and Center were then, as now, intent on focusing the discussion on institutional interest, archival means, and public access.

Those concerns rang true, as it had done for other families of authors. Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York and at the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, may have had the most prescient words on the matter:

Financial, preservation, and access considerations often trump ideological ones. Families will gravitate to places that care about the work.

This is such an emotional decision. It’s about trust — you’re giving your family member’s history and legacy to strangers. Families need a lot of reassurance about both preservation and access.

Many times, it is not the writer that makes the decision to sell or donate the papers to a particular library or site.

[And García Márquez’s] creative life largely unfolded outside of Colombia. He was also influenced by American writers and had personal ties to the US.

You can argue about where it should go, but there needs to be something to argue about. Once you lose these types of materials, certain types of inquiry become impossible. We need to preserve them so that we can ask more and more complex questions about our past — that’s the bottom line.

— Frances Negrón-Muntaner, 2014

One is tempted, given the context above, to see the early digitizing of García Márquez’s papers as partly emanating from this conversation, or at least from similar concerns the family and Center might have been aware of and discussed. Though institutions with means throughout the world are increasingly digitizing — and making freely available — their author collections and archives, it remains highly unusual for that process to be undertaken for literary collections this early into post-humous copyright protection, and furthermore for material that has not been officially published. Families are more often counseled to view the present and future commercial interests of an author’s estate to be in conflict with those of free public access for scholars and fans, with a not unexpected risk of wide republication of those materials.

Viewed in this light, Rodrigo García’s recent comments bear significant weight. They seem to make clear both the family’s decision on the matter and its general approach to the papers’ preservation and use.

Plus, the stance, shared with the Center, may have fostered further technical innovation in archival processing and access. Funded by a CLIR grant, the digital archive project is entitled Sharing ‘Gabo’ with the World: Building the Gabriel García Márquez Online Archive from His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center. And one of its notable features is the Mirador image viewer it provides, allowing scholars, students, and fans to select and compare pages side-by-side, and thus develop a sense of how García Márquez’s novels and short stories evolved. The capability is made possible by the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), whose implementation places all images from the online archive on an accessible, international network of IIIF-enabled digital image collections.

Liz Gushee, head of Digital Collections Services at the Ransom Center, describes the feature as one of several in a project intent on “fostering new methods of use and scholarship of archival materials. It provides rights-holder-approved online access to copyright-protected archival materials.” And it further creates, she adds, “opportunities for comparative research and interoperability with other IIIF-compatible online collections. The support from García Márquez’s family made this important project possible.”

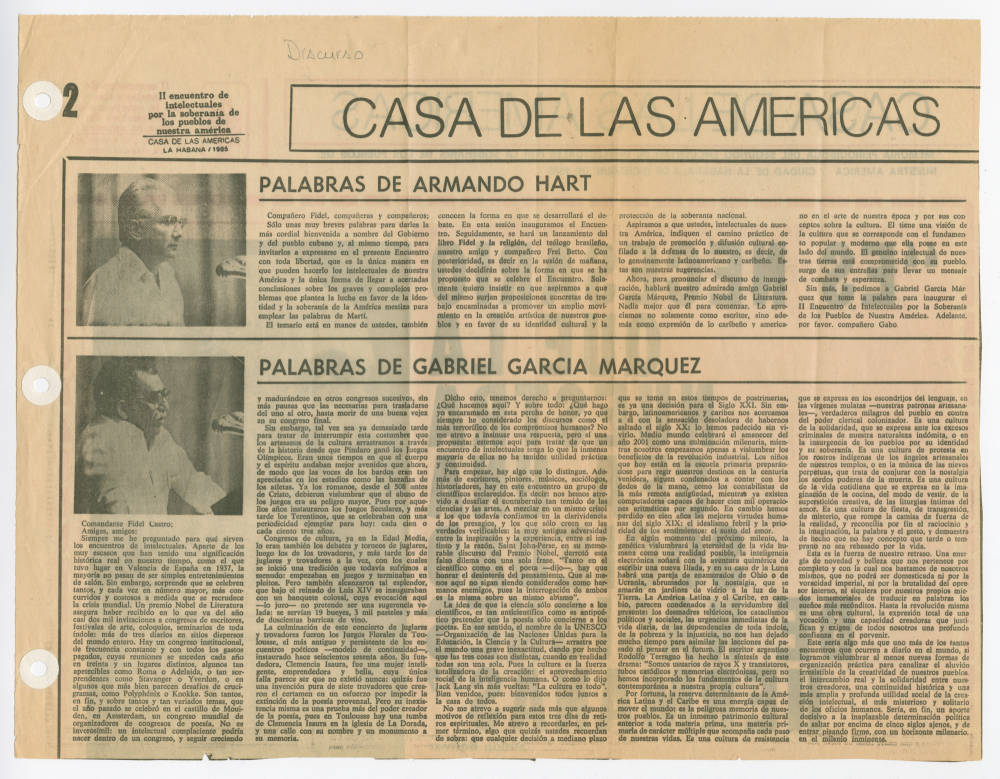

Palabras Para Un Nuevo Milenio

One benefit of these features that the Center’s archivists and specialists seem intent on tempting us with concern the perenniel project, undertaken by aficiandos and scholars alike, of unravelling the creation myths behind the construction of novels. García Márquez was a well known fabulist of the process itself, and this trait was often on full display when asked about the lead up to the publication of his best known work, One Hundred Years of Solitude. It turns out, the author’s stories of crafting the novel in a zone of uninterrupted inspiration (“I did not get up for 18 months,” he is known to have said) is dutifully contradicted not just by the drafts in the archive, but also by his correspondence with several trial readers, an informal but expressly cultivated constellation of focus groups, as it were, to whom he sent sections and whose reactions led to adjustments.

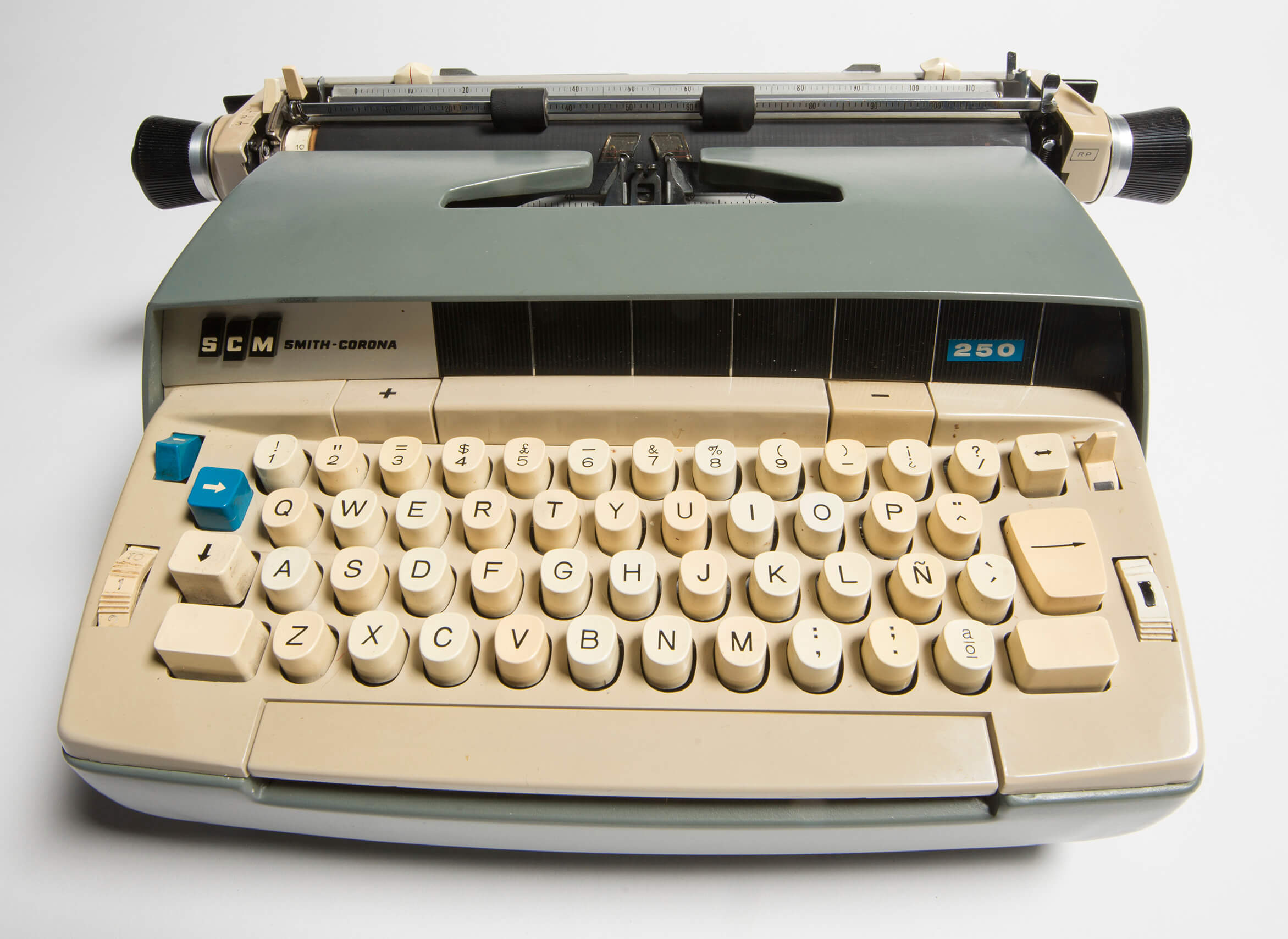

Also, his declared practice of destroying, or at least not retaining, drafts themselves was gently thwarted by his wife and at times his secretary, during periods when they took up the routine, near daily task of incorporating corrections he made as he reread typescripts. Several of those typescripts were retained, as well as the new, stand-alone drafts the revisions were meant to produce.

Manuscript and Nobel Ticket

And there is the topic of the novel’s progressively fine-tuned plot, settings, and spans of time. Perusing interviews he gave to periodicals, like El Nacional, provides a visitor of the archive with a fuller picture of a writer who revised obssessively and continuously, altering major aspects of the novel, often while making seemingly definitive pronouncements about its length, movement, chronology, towns, major and minor protagonists. At one phase of its drafting, the novel was meant to span five centuries — not the one of its eventual title — and the Caribbean town of its primary setting, Macondo, was meant to end up transforming into an “enormous and hot African city.”

Suffice to say, for students of the novel who have sought to further uncover its connections to Caribbean and African culture, as well as for those writing future novels with the image of spontaneous, near-magical inspiration in mind, a visit to this archive (in person and online) will likely be seen as their own kind of treasure trove, a means of amplification and correction, and a possible point of return, for the more researched guidance and inspiration that allows them to continue the best versions of their work. For this opportunity, too, we thank the García Márquez family. And ‘Gabo’ most of all.